Stranded By The Pandemic

I hadn’t planned to spend most of 2020 stuck in a tiny apartment in Adelaide with my 81-year-old mother and a cat. My mother hadn’t planned it either (nor, presumably, had the cat).

Stranded in Australia by the pandemic, I found myself not only separated from my Dublin-based husband of 30 years but also living with my Mum for the first time since I was a teenager.

When I’d said goodbye to John at Dublin Airport last February, I expected to see him again in four weeks. After decades of moving between Dublin and Australia (my birthplace), I was used to these flying trips to see family and publishers.

And then Covid intervened. My return flight to Dublin was cancelled abruptly in March and I found myself stranded indefinitely in Adelaide.

I unpacked in the tiny spare room of Mum’s cramped city-centre apartment. It was a long way from my childhood home in the station master’s big house in the country town of Clare, filled with six brothers and sisters, a constant stream of relatives and visitors. Three years after Dad’s death in 2000, Mum had moved to the city, into a series of progressively smaller houses.

In the 38 years since I’d left home, I’d moved interstate and overseas. I’d returned often, breezing in and out, enjoying fast-paced family gatherings, snatched conversations, dipping in and out of Mum’s life, before yet another airport farewell.

‘Can I stay here indefinitely?’ I asked her now. I still don’t know if I imagined a faint hesitation.

Early on, I became over-zealous in my role as Mum’s Covid-protector. With my family’s backing, I declared she had to stay inside while I shopped and cooked. I regularly reminded her to sanitise. I disinfected every surface, moving her books and crosswords out of the way. All the while, I spoke about missing my husband; being homesick for Irish friends, weather, radio, theatre; how small her apartment was; how my life had turned upside down; poor me, so far from home and –

‘This is hard for me too, Monica,’ she interrupted one April day, in a firm tone that sent me spinning back to childhood. ‘Having you here, after living on my own.’

But I’m one of your children, I wanted to wail. You must love having me back.

I retreated to the tiny bedroom, stung. I rang my sisters and complained. I lay awake. I thought about my constant bossing, cleaning, re-arranging. My belongings taking up space in every room. Mum’s peaceful, independent life turning overnight into a sharehouse.

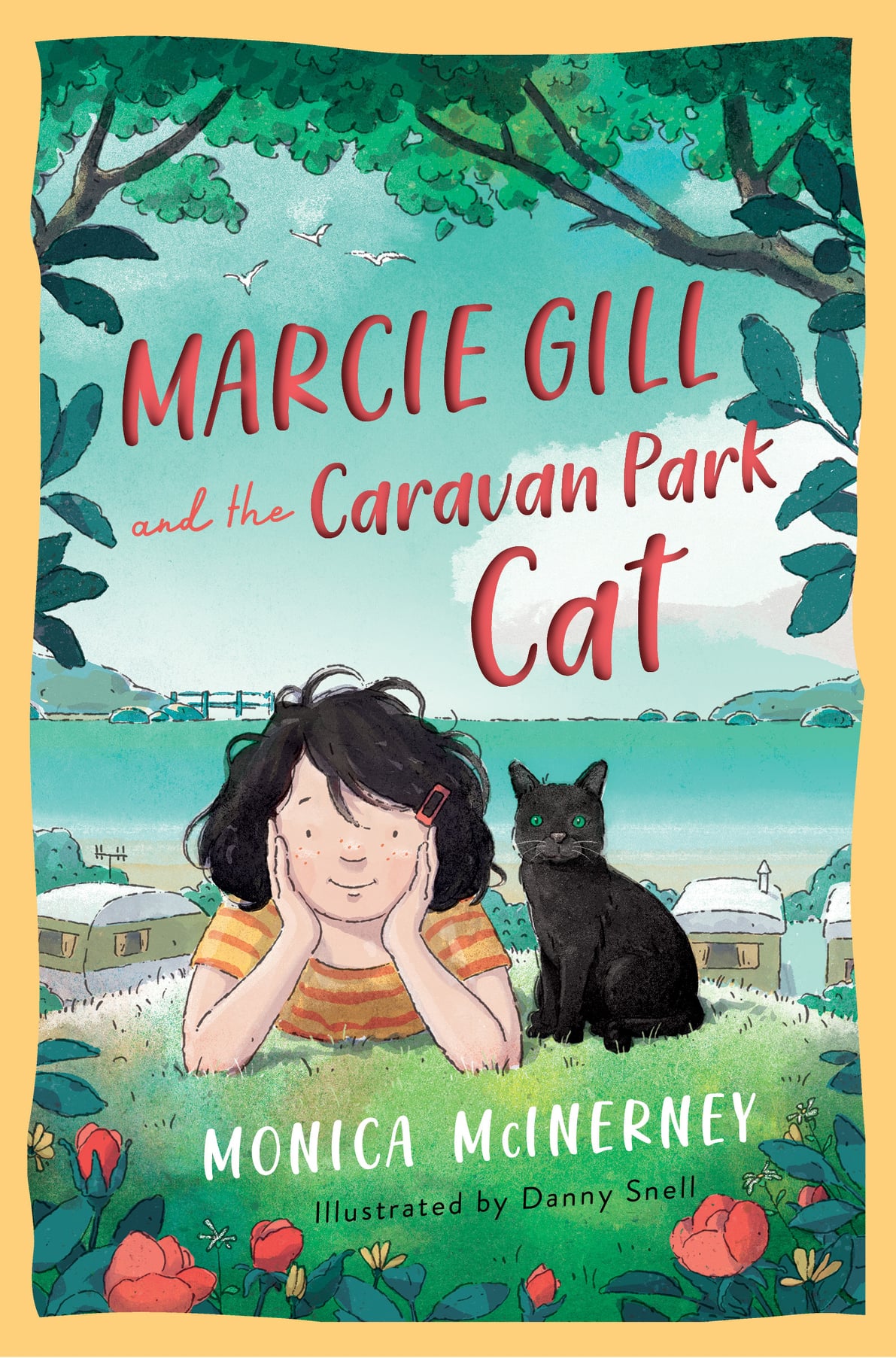

I apologised. But there was still tension. It was my sister’s idea to adopt a rescue kitten. With the world outside uncertain, the mood inside sometimes tricky, Mum and I discovered a half-wild black scrap of a cat provided not only distraction, but endless entertainment too. We named him Nicholas, after Mum’s Irish grandfather.

All the while, I kept working. There was just enough space in Mum’s spare room to set up a desk, squeezed between the bed and clothes-rack. I finished editing The Godmothers, spreading the pages out on my single bed. I began writing articles to accompany October publication in Australia.

The Godmothers is a family mystery, following 30-year-old Eliza Miller as she searches for the truth about her late mother’s troubled life and the father she’s never met.

It was partly inspired by my fascination with the mysterious death of my father’s half-sister. She drowned, aged 44, in an underground water tank on the family farm in 1957. Growing up, I always felt there was more to it than an accident. Had it been suicide or something more sinister? My father said he didn’t know more, but I always suspected my own godmother – Dad’s other sister – did. Try as I might, however, I could never get her to share a detail. “All that generation was now gone, their secrets with them,” I wrote in an article one morning.

I asked Mum to read an early draft. ‘We’d just got engaged when it happened,’ she remembered as she finished reading. She described in detail a visit to the farm, how another aunt had turned on her. ‘Never mention it again to anyone, do you understand?’ She spoke about the drowned aunt’s life, my father’s complicated family, his sisters. A shadowy childhood story sprang into technicolour. I added unexpected details to my article.

I felt like I’d been given the key to a treasure chest. This wasn’t like my usual trips home, a flurry of gatherings, snatched conversations. Every day, Mum and I had hours to talk, in between my writing and her reading, crosswords and online Scrabble. I learned to choose my times carefully, wait for peaceful moments, not bombard her with questions. She started telling stories I’d never heard before.

I discovered that Mum and Dad, both grandchildren of Co Clare emigrants, had danced for the first time at a St Patrick’s Day ball in Mum’s home-town. That as a 17-year-old Mum lived for several months in an Adelaide hostel for young ladies, working as a telephonist at the GPO. I listened as she described her relationships with her three sisters and three sisters-in-law. She spoke about her marriage, about my Dad’s life and death, about becoming a mother to the seven of us, the great sadness of two miscarriages. Often, we’d lie talking on her double bed looking out at the sunset, as Nicholas played or slept between us. I’d lie in the half-light, gathering every detail into my memory.

I was soaking up not only her stories, but also her wisdom, hard-earned over eight decades. I kept noticing how calm she stayed. How she said what needed to be said, then moved on. She had a serenity I yearned for.

I would never have thought it possible to step out of my own life into hers for nine months. To move from being one of her children to seeing her as an adult woman. To recognise my own shortcomings – anxiety, impatience, bossiness – and be shown other ways to live and behave.

I’d booked a return flight to Dublin for mid-November, hopeful it would be possible. But 2020 had another plot twist. The flight was cancelled due to unexpected family reasons. Instead, my husband was granted an exemption to travel to Australia. After his fortnight hotel quarantine, we were finally reunited, not on a cold Irish winter’s day, but on a hot Adelaide morning.

We’re not living in Mum’s tiny spare room. For all our sakes, we rented an apartment. There’s only one area of tension between Mum and I now. She kept the cat. I’m trying to be grown up about it.

(First appeared in The Irish Times)